School Administrative Workload: Why It's Worse & How to Fix It

Brian McManus - September 14, 2025

Imagine an assistant principal arriving at school before sunrise. Before the first bell rings, they've already managed three parent emails, found coverage for a sick teacher, reviewed disciplinary reports from the previous day, and mediated a conflict between two staff members. This feeling of being trapped in a cycle of reactive management is a universal experience, and the data confirms it: a majority of school leaders report spending more than six hours a week on administrative paperwork (NASSP). This constant pressure isn't just about managing tasks; it's taking a profound human toll. A staggering three-quarters of school leaders (73%) report they needed help with their mental or emotional health last year (NASSP+2). This isn't a personal time management issue; it is the direct result of a systemic evolution of the role over the past two decades, driven by policy shifts and societal pressures. This article will validate that experience by tracing the historical roots of the modern administrative workload, using research to show how the job has fundamentally changed and setting the stage for a new way of thinking about the role.

For 15 of my 20 years in education, I would roll my eyes internally whenever a seasoned educator complained about the workload "back in the day."

For 15 of my 20 years in education, I would roll my eyes internally whenever a seasoned educator complained about the workload "back in the day." When I started teaching English at a large high school, No Child Left Behind was the only reality I knew, and from my vantage point, its impact was minimal. My eye-roll was due to ignorance. It wasn't until I moved into administration that the work became Sisyphian. The daily cycle of observation reports, board communications, substitute coordination, and lunch duty felt like pushing a heavy boulder up a mountain, only to watch it roll back down each morning. The "other stuff" started to define my role; instead of being in classrooms or meeting with knuckleheaded teenagers who made poor choices, I spent more time in my office pushing that boulder. Were the old-timers correct? Do my eyes owe them an apology?

The intensification of the school administrator's workload is not merely a perception but a well-documented phenomenon in educational research. Foundational reports have established that school leadership is second only to classroom instruction in its impact on student outcomes, highlighting the critical nature of the principal's role (Leithwood et al., 2004). However, the capacity to perform the high-impact functions of this role has been progressively eroded. The shift began in earnest with federal accountability mandates that fundamentally altered the job's focus, burying leaders in bureaucratic tasks that divert their attention from the core mission of supporting teaching and learning (Horng et al., 2010).

From Instructional Leader to Chief Problem-Solver: A 20-Year Shift

The role of a school administrator has morphed from a primary focus on curriculum and instruction to a complex, multi-faceted position centered on compliance, crisis management, and public relations. This shift in school leadership over the past 20 years has left many principals and assistant principals feeling like they are responding to an endless series of urgent problems rather than proactively shaping the educational leadership and culture of their schools. Research clearly shows that this transformation is a direct consequence of escalating external pressures, from federal policy to community politics, which have redefined the core responsibilities of the job.

This isn't just about policy; consider the role technology now plays in our schools. It has become intertwined with every curricular decision, and it’s expensive and messy. Acceptable Use Policies, proxy servers, inventory, maintenance, and connectivity are all burdens on administrators.

We not only need to ensure students are compliant with district policies, but also that every piece of technology is being leveraged to positively impact student achievement. i-Ready, anyone?

The Principalship in the Pre-Accountability Era: A Different Focus

Two decades ago, the principal was largely seen as the head of the school building, a role centered on operational management, staff oversight, and fostering a positive school climate. The primary focus was on creating an orderly environment conducive to learning, with instructional leadership often taking the form of periodic teacher evaluations and curriculum oversight. While demanding, the role was more circumscribed, with fewer external mandates dictating the day-to-day allocation of a principal's time and energy (Darling-Hammond, 2007).

Finding a balance between leadership and management today is challenging when the managerial aspects are often the key deliverables for a school district. Generating reports for the central office, managing ever-shrinking budgets, and navigating new cultural mandates—all of these pressures have an impact on school leaders that flows down to teachers and, ultimately, to students. An assistant principal who spends every morning cursing the substitute coverage crisis is not in the optimal mindset to be an instructional leader. That stress has an impact.

How Policy and Technology Increased Mandates Without Increasing Hours

The most significant driver of change was the accountability movement, beginning with the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) in 2001 and continuing with the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) in 2015. These federal laws tied school funding and evaluations to standardized test scores, compelling administrators to become data analysts and compliance managers (Darling-Hammond, 2007). The rise of technology, while offering tools for efficiency, also created an expectation of constant availability and instantaneous reporting, adding to the pressure without adding hours to the day. This policy-driven shift dramatically increased the volume of "bureaucratic" administrative tasks, pulling principals away from classrooms and into offices to manage paperwork and reporting requirements (Horng et al., 2010).

This has led to a "compliance-oriented culture" where the focus can shift from holistic student development to narrowly defined, test-based outcomes (Au, 2011).

The Data Dilemma: How the Push for Student Achievement Metrics Bloated Administrative Tasks

The emphasis on student achievement metrics, while intended to promote equity, created an enormous administrative burden. School leaders now coordinate extensive testing schedules, analyze vast amounts of performance data, and develop detailed improvement plans. This has led to a "compliance-oriented culture" where the focus can shift from holistic student development to narrowly defined, test-based outcomes (Au, 2011). Consequently, principals spend significant time in data meetings and completing reports, which directly trades off with time that could be spent on instructional coaching and teacher development (Grissom et al., 2013).

Perhaps the worst part of the accountability movement has been the proliferation of online, adaptive learning platforms that collect every conceivable data point. Programs like i-Ready, IXL, and Aleks provide hundreds of metrics, and frankly, it's too many. Which of these data points truly impacts student learning? I can't say for sure, but I also can't begin to estimate the hours I've spent in data analysis meetings trying to find out. I am not suggesting student data shouldn't be analyzed. But the sheer volume of it, and the time it takes to make sense of it, is a monumental time drain for both teachers and administrators.

What Is the True Cost of the Modern Administrative Workload?

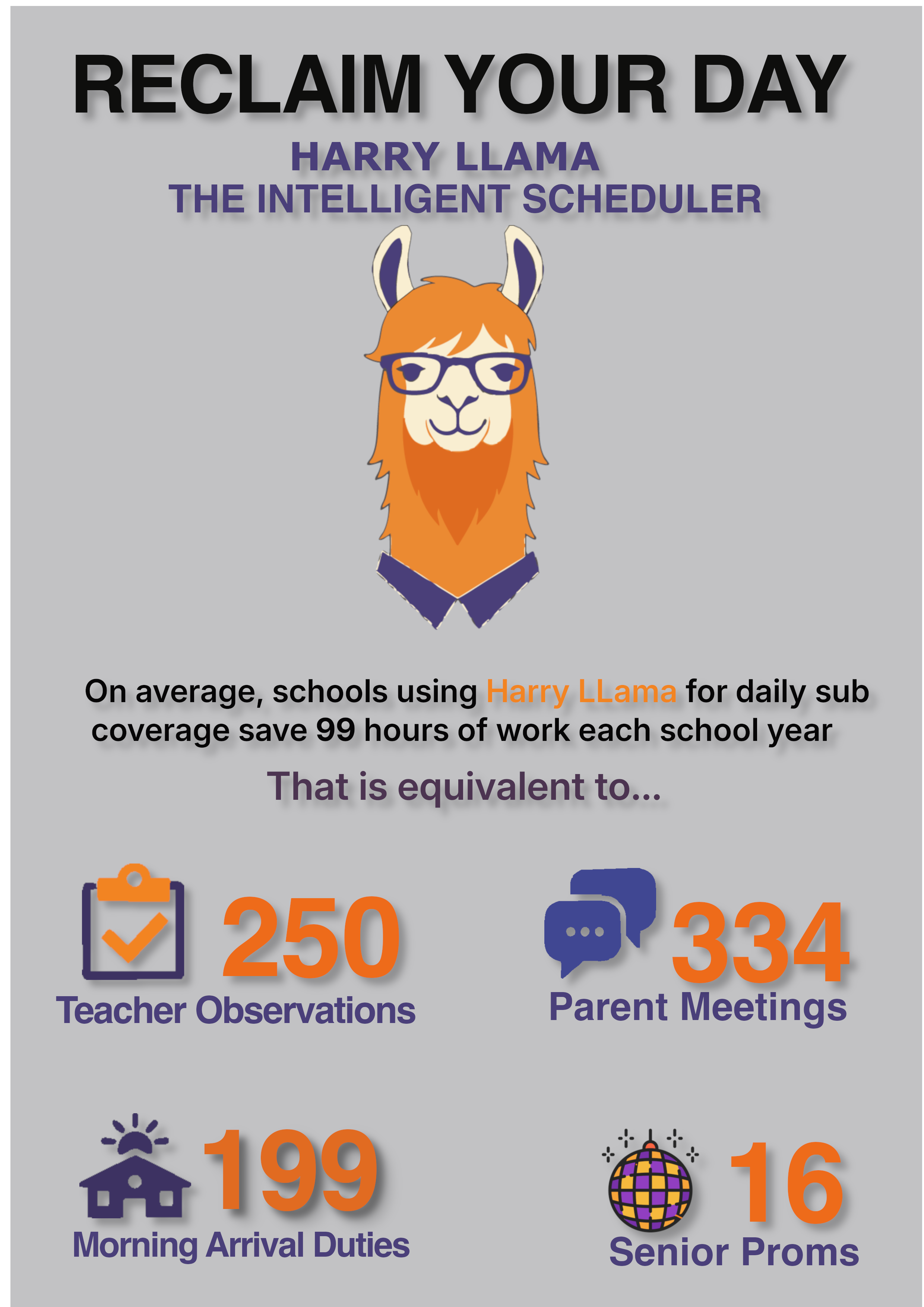

The true cost of the bloated administrative workload schools face is measured in lost instructional time, diminished leader effectiveness, and ultimately, a negative impact on the school community. When administrators are mired in operational minutiae, they cannot focus on the activities proven to drive school improvement. The cost of manual substitute teacher scheduling, for instance, is not just a line item in a budget; it represents hours of lost leadership capacity every single day.

Discover how manual substitute teacher scheduling costs your school $5,800+ annually. Calculate your hidden costs with our free "Salary Spent on Sub Coverage" calculator.

Answering the Question: What is the cost of administrator time on substitute coverage?

The persistent substitute teacher shortage has turned daily staffing into a crisis. This task is no longer a simple clerical duty but a time-consuming daily scramble that involves personally calling potential subs, rearranging schedules, or even covering classrooms (Gewertz, 2023). Calculating the true cost requires factoring in the administrator's salary for hours spent on this low-leverage task, the opportunity cost of lost instructional leadership during that time, and the risk of principal burnout as leaders are pulled from their core duties to fill gaps.

The Black Hole of Manual Processes: A Deep Dive into Substitute Teacher Scheduling

Why is substitute teacher scheduling so difficult? The difficulty arises from a shrinking pool of substitutes, a lack of integrated technology, and the unpredictability of absences. The infamous Friday substitute teacher rush is a real phenomenon, as absences often spike at the end of the week. This manual process forces administrators into a reactive mode, consuming critical morning hours that effective principals would otherwise dedicate to instructional leadership activities like classroom walkthroughs (Horng et al., 2010).

During my six years as an assistant principal, I spent far too many mornings figuring out who was going to cover a first-block class—and it was usually me. I vividly remember one Wednesday morning with a modified bell schedule. We had 23 teachers absent, a department-wide PD, and two child study meetings that all required coverage. I was juggling three different spreadsheets when a teacher called to say their car broke down. That morning, I covered three different classes simultaneously in the cafeteria. Later, I did the math: over the course of a school year, I spent roughly 114 hours just solving the substitute puzzle. As I cursed the second spreadsheet while walking to the cafeteria, I couldn't help but wonder what those hours could have meant for my ability to be an effective instructional leader.

Assistant Principal Instructional Leadership: From Administrative Overwhelm to Educational Impact

The Impact on What Matters Most: Instructional Leadership and Burnout

The relentless expansion of administrative duties has a direct and damaging impact on instructional leadership and the well-being of school leaders. As the scales tip toward managerial tasks, the time available for high-impact activities like teacher observation shrinks, and the risk of principal burnout skyrockets. This creates a vicious cycle where stressed leaders are less effective at supporting their teachers, which in turn can negatively affect student learning.

The Core Conflict: What is the difference between a manager and an instructional leader?

A manager focuses on operations—budgets, schedules, compliance. An instructional leader focuses on the core technology of schooling: teaching and learning. Research makes a clear distinction; effective principals engage in classroom observations, provide substantive feedback, and foster professional collaboration (Grissom et al., 2013). The modern workload forces administrators into a managerial posture, fundamentally conflicting with the instructional leadership behaviors known to improve student achievement (Horng et al., 2010).

My ideal day as an assistant principal was simple: welcome students, visit classrooms, conduct observations, have professional conversations with teachers, and make positive phone calls home for students who had a great day. My typical day, however, left little time for any of that. My time was focused on putting out fires, not being an instructional leader.

The Impact on Assistant Principal Instructional Leadership and Meaningful Feedback

With calendars packed, deep, meaningful teacher observation cycles are often replaced by brief, superficial "check-ins." The time needed for substantive pre- and post-observation coaching is a luxury many administrators can no longer afford. This erosion is a critical loss, as a principal's ability to provide high-quality feedback is a key driver of school improvement (Grissom et al., 2013). When an assistant principal's day is consumed by discipline and operations, their capacity for assistant principal instructional leadership is severely compromised.

The Unseen Toll: Connecting the Dots Between an Overwhelming Workload and Principal Burnout

The combination of an intensified workload, expanded SEL responsibilities, and heightened political pressures has led to a crisis of principal burnout. Administrators are increasingly caught in the crossfire of contentious community debates, adding significant emotional labor to the job (Force, 2022). This unsustainable pressure contributes to high turnover rates in school leadership, which destabilizes entire school communities (Fullan & Quinn, 2021).

There were nights I couldn't sleep because I knew the next day's sub schedule was going to be like putting together a 1,000-piece jigsaw puzzle of a black sky. I'd walk into school with a metallic taste in my mouth, using language that I was thankful my office door muffled. It deeply impacted my mental health. I didn't want to be a substitute scheduler; I wanted to be an assistant principal who worked with teachers on their craft and helped students learn to engage with society. Instead, I became a big ball of anxiety, which didn't help anyone.

The Invisible Crisis: Principal Burnout and How to Prevent It

A Systemic Problem Demands a Systemic Solution: How Schools Can Reduce the Administrative Workload

The question of how can schools reduce administrative workload cannot be answered with simple tips for better time management. The issue is not one of individual efficiency but of systemic overload. To truly reduce administrative workload for assistant principals and principals, schools must move beyond platitudes and implement systemic solutions that reclaim time for instructional leadership.

To effectively reduce the administrative workload for assistant principals, schools need systemic solutions, not just better time management. This approach is crucial for preventing principal burnout and creating space for effective school leadership. The key is to leverage administrative process automation for schools, such as substitute management software, to handle repetitive administrative tasks. Automating daily substitute teacher scheduling, for instance, frees leaders to focus on high-impact assistant principal instructional leadership strategies that directly improve student achievement.

Moving Beyond "Work Smarter, Not Harder

For two decades, school administrators have been told to "work smarter, not harder," a phrase that ignores their ever-expanding job descriptions. The problem is not a lack of effort but a lack of hours. The literature shows that the overload is well-documented, but there is a significant gap in research that tests scalable solutions (Spillane, 2005). True solutions must acknowledge the systemic nature of the problem and focus on changing the system itself, not just asking individuals to manage an unmanageable workload more efficiently.

Leveraging Systems and Technology to Automate the Automatable

A key strategy for systemic change is the intelligent use of systems and technology to automate or delegate non-instructional tasks. This could involve adopting distributed leadership models, where responsibilities are shared among a team (Spillane, 2005). Furthermore, schools can leverage modern software to handle tasks like substitute management and parent communication. Wrestling with antiquated or non-existent substitute management software is a prime cause of the daily scramble that can be automated away. By strategically automating routine operational duties, districts can buffer principals from the bureaucratic tasks that consume their days and allow them to focus on the instructional leadership that improves teaching and learning (Horng et al., 2010).

Ready to start reclaiming your time? Get a practical framework with our 90-Day Plan to Reclaim Your Instructional Leadership Time

Conclusion

Key Takeaways:

- The administrative burden on principals and assistant principals is not a personal failing but the result of a 20-year systemic shift driven by accountability mandates and expanding societal expectations.

- Manual, time-consuming processes, such as daily substitute teacher scheduling, directly erode the time and energy available for high-impact assistant principal instructional leadership.

- The solution to this crisis lies not in asking leaders to manage an impossible to-do list more efficiently, but in fundamentally redesigning school operations with systems and technology to protect the role of the instructional leader.

Ready to Reclaim Your Day?

About the Author:

Brian McManus is an educational leader with over 20 years of experience in public schools, including six years as a high school Assistant Principal. After spending more than a decade witnessing firsthand how systemic pressures and manual processes were pulling school leaders out of classrooms and away from instructional leadership, he dedicated himself to finding a better way. Frustrated by the daily scramble of substitute scheduling and bureaucratic overload that defined his role, he founded Lucid North and developed Harry Llama - The Intelligent Scheduler. The firm focuses on developing systems and strategies that empower administrators to automate low-impact work, reduce burnout, and reclaim their time for what matters most: improving teaching and learning.

References

-

Au, W. (2011). Teaching under the new accountability: High-stakes testing and the professional lives of teachers. Journal of Curriculum and Pedagogy, 8(2), 191-209. URL / DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2010.521261

-

Darling-Hammond, L. (2007). Race, inequality, and educational accountability: The irony of ‘No Child Left Behind.’ Race Ethnicity and Education, 10(3), 245-260. URL: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ774902

-

Gewertz, C. (2023). The substitute teacher crisis: How it's hurting schools and what can be done. Education Week, 43(4), 1-15. https://www.edweek.org/leadership/opinion-were-facing-a-looming-crisis-of-principal-burnout/2021/10

-

Grissom, J. A., Egalite, A. J., & Lindsay, C. A. (2021). How principals affect students and schools: A systematic synthesis of two decades of research. The Wallace Foundation. URL: https://www.wallacefoundation.org/principalsynthesis

-

Grissom, J. A., Loeb, S., & Master, B. (2013). Effective instructional time for teachers: A key to school improvement. Educational Researcher, 42(8), 415-422. URL / DOI: https://cepa.stanford.edu/content/effective-instructional-time-use-school-leaders-longitudinal-evidence-observations-principals

-

Horng, E. L., Klasik, D., & Loeb, S. (2010). Principal's time use and school effectiveness. American Journal of Education, 116(4), 491-523. URL: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/28151/1001441-Principal-Time-Use-and-School-Effectiveness.PDF

-

Leithwood, K., Louis, K. S., Anderson, S., & Wahlstrom, K. (2004). How leadership influences student learning. The Wallace Foundation. URL: An overview and link to PDF report summary: https://www.wallacefoundation.org/sites/default/files/2023-10/Investigating-the-Links-to-Improved-Student-Learning.pdf

-

McManus, B. (2025, 09 08). Save $5,800: Assistant Principal Instructional Leadership. Lucid North's Dispatches from the Llama. https://lucid-norths-dispatches-from-the-llama.ghost.io/ghost/#/editor/post/68bdcaf6b5154900017f7e71

-

Robinson, V. M. J., Lloyd, C. A., & Rowe, K. J. (2008). The impact of leadership on student outcomes: An analysis of the differential effects of leadership types. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(5). URL / DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X08321509

Member discussion